DVD REVIEW

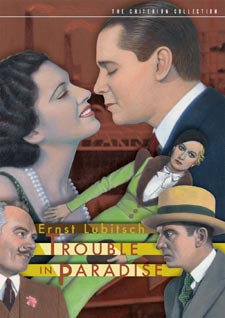

Year: 1932. Running time: 82 minutes. Black and white. Directed by Ernst Lubitsch. Starring Herbert Marshall, Miriam Hopkins, Kay Francis, Charlie Ruggles, Edward Everett Horton, and C. Aubrey Smith. Adapted by Grover Jones from the play by Aladar Laszlo. Screenplay by Samson Raphaelson. Aspect ratio: 1.33:1. DVD release by The Criterion Collection. Review by Kendahl Cruver When Trouble in Paradise was first released in 1932, neither critics nor

audiences paid much attention. The sophisticated comedy did not appeal to a

population bearing the brunt of the Depression. They preferred escapist

movies such as jungle melodrama Red Dust and the sentimental romance

Smilin' Through.

The film still hadn't made a profit in 1935 when the Legion of Decency rated

it Class I (the most severe ranking) and it was denied re-release. In the

years since, it has only been accessible through rare screenings and thus

unavailable to a general audience.

Despite its difficult past, Trouble in Paradise has enjoyed a remarkably strong

reputation among film fans in recent years; it even won a spot on the

National Film Registry in 1991. Many difficult-to-see films have built up a

reputation only to disappoint when they are finally readily available. Now

that it has been released on DVD, it is clear that this is not the case with

Trouble in Paradise. Its sleek charm has not lessened in the decades since its first

release.

The plot revolves around a love triangle. Lily and Gaston (Miriam Hopkins

and Herbert Marshall) are thieves who meet on the job. They are delighted to

catch each other in the act and their crimes become an act of seduction.

After a year together, they find that the Depression hurts criminals as much

as the working class.

When Lily and Gaston meet Madame Colet (Kay Francis), a perfume heiress in

search of romantic thrills, they sense an opportunity to better their

fortunes. Gaston wins a job as her secretary and Lily becomes his assistant.

With his eyes on her safe, Gaston initially responds to Colet's brazen

flirtation as a part of the ruse, but he quickly finds that he really does

have feelings for her. Lily worries not only that she will lose him but

that he will stop stealing and become a good for nothing gigolo.

Hopkins, Marshall, and Francis did some of their best work in Trouble in Paradise.

Lubitsch was one of the few directors (William Wyler is another) who was

able to harness Hopkins' tendency to chew scenery. Francis was more famous

for being a clotheshorse and having trouble saying her r's than acting, but

as Madame Colet, she exudes a wistful air with unusual delicacy. In the

course of his career, Marshall would not often vary his restrained

mannerisms, but here he seems less uptight and more elegant.

Lubitsch owed part of his success with actors to his own experience as a

young actor in Germany. He would act out exactly what he wanted in each

scene. Occasionally he would even wear women's clothing so that he could get

the body language right. He would also expand small roles in his films,

putting a spotlight on the kind of part that he used to play himself. This

is evident in the special attention Colet's baffled butler receives.

As his previous film, One Hour with You had lost money, Lubitsch was

forced to film with economy, and these restrictions ultimately helped the

film. He juggles dialogue and visuals, often limiting one to increase the

effect of another. For instance, on a pivotal night when Lily warns Gaston

not to succumb to Colet's advances and he slowly does so anyway, the actors

do not appear onscreen until the very end of the sequence. Instead, Lubitsch

focuses on a series of clocks, which mark the passage of a long night,

before resting on an empty bottle of champagne in a bucket of melted ice.

In another instance, he shows several conversations at a garden party, but

the dialogue cannot be heard because the actors are filmed through a large

windowpane. By paring down scenes in this manner, Lubitsch elegantly avoids

explaining too much.

Lubitsch also trades between images and dialogue to show the differences

between the two women Gaston loves. Gaston has more dialogue with Lily

because he is candid with her. He knows they are so similar that he cannot

hide anything from her anyway. She is lovely, but he is most attracted to

her skill and he uses words to seduce her. While she lies supine on a couch,

he calls her his "little shoplifter."

From the moment Gaston meets Colet, it is images and surface beauty that he

finds attractive and which enable him to seduce her. He advises her on

cosmetics, exercise, and diet and she gratefully accepts his advice, though

she does not always follow it. When they embrace, Lubitsch films them

reflected in mirrors and in silhouette, as if to emphasize the superficial

nature of the affair. Gaston himself is increasingly shown in reflection or

through windows, as he becomes more deeply involved with Colet.

In the end, Gaston proves that there can be honor among thieves and it is

Lily who best understands his point of view. Colet is only quietly saddened

that outsiders have robbed her, but she has difficulty accepting that the same

deception can exist in her luxurious world. Only Lubitsch could make all

this pain, deception, and revelation seem so delicious.

The Criterion Collection's DVD has been engineered to remove snaps and

crackling on the soundtrack and the picture quality is as good as the sound.

The introduction by director Peter Bogdanovich is interesting primarily due

to his acquaintance with many important figures of classic Hollywood and his

insight into their lives. The package includes an early silent film directed

by Lubitsch, a collection of written tributes from critics, directors, and

other film peers and a dry, but informative commentary track. There is also

an amusing radio program on the disc starring Lubitsch, Jack Benny,

Claudette Colbert and Basil Rathbone.

Trouble in Paradise is now available on DVD from The Criterion Collection in a new digital transfer with restored image and sound. Special features: audio commentary by Lubitsch biographer Scott Eyman (Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise); video introduction by Peter Bogdanovich; Lubitsch' silent film Das fidele Gefangnis (The Merry Jail, 1917) with Emil Jannings, featuring a new score recorded exclusively for this release; 1940 Screen Guild Theater radio program featuring Ernst Lubitsch, Jack Benny, Claudette Colbert, and Basil Rathbone; and tributes to Lubitsch written by Billy Wilder, Leonard Maltin, Cameron Crowe, Roger Ebert, and others. Suggested retail price: $39.95. For more information, check out the Criterion Collection Web site.

|