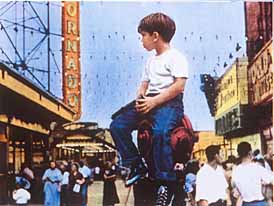

Richie Andrusco in Little Fugitive.(©1997

Kino on Video. All rights reserved.)

|

It’s not hard to see why Little Fugitive, their most famous and successful film, was so inspiring not only to the French, but also to American auteurs like Cassavettes (Shadows) and Scorsese (Who’s That Knocking on My Door?). Like the two features that would follow it, Little Fugitive is a paean to the sights, smells, and sounds of New York, from the cramped but somehow comforting streets of Brooklyn to the dazzling chaos of Coney Island as seen through a child’s eyes. Engel and Orkin extrapolate the universal from the personal in this Homeric story of a little boy’s heroic trek alone through the vastness of an urban amusement park.

The "fugitive" of the title is Joey Norton (Richie Andrusco), a seven-year-old from Brooklyn who’s left in the care of his 12-year-old brother Lennie (Ricky Brewster) when their mother is called away on an emergency. Lennie and his friends are sophisticated pranksters, and they pull what turns out to be a potentially deadly joke on Joey: they let him shoot a "real" gun and convince him that he’s killed Lennie and that the cops will be after him. Far from the cliché imagery of sweet, obedient 1950s children, these kids have a vicious black-comic edge: "They’ll sure give Joey the electric chair—he’ll fry!" one says. The terrorized Joey grabs the money his mother left for him and Lennie and runs off to Coney Island.

When Engel interviewed Richie Andrusco for the part of Joey, he noticed what he called an "animal strength" in the boy that made him right for the part. This quality is certainly evident as Joey, dwarfed by the teeming crowds, whirling neon, and boundless expanse of sand, moves through his ordeal with what can only be called aplomb. Not that there are overt threats—the crowds are mostly indifferent as he marches along collecting bottles to redeem for pony rides, or wriggles into a group of adults throwing balls at milk bottles, demanding his chance to play. Witty anecdotal touches abound. In a bathroom reference of a kind that was de rigeur in Italian neo-realism, Joey drinks too much Pepsi and is desperate to relieve himself; when he comes upon a sign that says MEN, he gratefully traces each letter.

The film’s breathtaking, often painterly visuals add resonance to the tiniest details—two toddlers grappling with each other on the beach; a couple making out on a blanket, their faces unseen; a mother spilling her child’s milk. These shots seem at once casual, real, and artful, as if in recording the simple truth of an event the filmmakers have stumbled upon art. There’s a stunning sequence of a sudden, violent storm that clears the beach, and the filmmakers take great delight in observing the chaos. Among those scrambling toward shelter are a group of black kids delicately stepping through the huge puddles on the street just beyond the beach. In a lovely wordless passage, Joey wanders across the beach after the storm, at night, dwarfed by the enormity of the world around him and, one feels, by his own future.

During the film’s initial release, some reviewers compared Richie Andrusco to Jackie Coogan, another way of reminding us that Little Fugitive recalls silent film. His wonderfully affecting performance, surely one of the reasons the film won Venice’s Silver Lion award in 1953, showed that it was not only possible but desirable for filmmakers to seek out "amateur" talent without the tics and mannerisms of trained actors. This strategy is verified in the freshness of the other performers, particularly Ricky Brewster as Joey’s droll but eventually regretful brother Lennie.

page 1 of 2

"The Films of Morris Engel With Ruth Orkin": The three videos comprising this set are available from Kino on Video. Suggested retail price: $79.95 for Little Fugitive and $39.95 each for Lovers and Lollipops and Weddings and Babies. For more information, we suggest you check out the Kino Web site: http://www.kino.com.

Gary Morris is the editor and publisher of Bright Lights Film Journal (http://www.brightlightsfilm.com). He writes regularly for the Bay Area Reporter and SF Weekly.

|

In the early days of cinema, before the rise of the Hollywood studios with their artificial, controlled environments in the form of sets and sound stages, movies took advantage of natural landscapes as backdrops for the narrative. These could be cityscapes, as in some of the early work of D. W. Griffith, or the great outdoors, as in the innumerable westerns that were a staple of pre-modern cinema. While there was clearly an economic motive in shooting on real locations, there was also a sense of connecting with audiences in a realistic way as the stories they saw unfolded in recognizable environments.

In the early days of cinema, before the rise of the Hollywood studios with their artificial, controlled environments in the form of sets and sound stages, movies took advantage of natural landscapes as backdrops for the narrative. These could be cityscapes, as in some of the early work of D. W. Griffith, or the great outdoors, as in the innumerable westerns that were a staple of pre-modern cinema. While there was clearly an economic motive in shooting on real locations, there was also a sense of connecting with audiences in a realistic way as the stories they saw unfolded in recognizable environments.