|

Footlight Parade features a waterfall scene in which hundreds of

scantily-clad bathing beauties slip and slide across an extravagant

pastoral scene replete with hills, dales and swimming pools. At one

point, two lines of women expertly float on their backs in the water and

paddle until their legs fit together like the pieces of a puzzle.

Another bathing-capped darling begins to swim through as the closed

lines divide in a gradual movement that looks like the spreading legs of

a hesitant young starlet. As the two lines come together again, we

realize that Berkeley has immortalized Judson’s "clasp-locker" in a true

homage to progress. He has zipped the most desirable zipper in

movie-making history. Berkeley continued to parade pretty powder-puffs

in his films, igniting desire in the hearts and genitals of the masses,

at a time when industry was the height of fashion.

Several years before Busby Berkeley began dazzling audiences with his dizzy blondes, Paris hosted the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriel Modernes of 1925. America didn’t participate in the Exposition because it claimed it didn’t have any modern art to speak of.

The turn of the century had proved to be a chaotic time of simultaneous innovation and destruction, most of which was afforded by the first World War. New modes of transportation were blurring perceptions of time and speed and drawing more attention to human creativity. The world needed new ways to express itself and artists responded with the clean shapes and colors of cubism. The cogs, sprockets, pistons and flywheels depicted in cubist works would serve to propel art through the murky beginnings of the twentieth century.

While the Exposition emphasized technological icons, shoppers in Paris’ major department stores soon found they could buy affordable home furnishings in the industrial style--soon to be known as "art deco." Purists were disgusted that consumers were decorating their homes with palatable abstract art and believed the mass-produced objects disguised the true meaning of their iconography. Designers argued in favor of this watered down version of cubism and claimed that a modern society should promote industrial production. While Europe debated the merits of new forms, materials and methods, America was obsessed with speed and progress. These elements were symbolically packaged in the hustle and bustle of "naughty, gaudy, bawdy, shoddy" New York City.

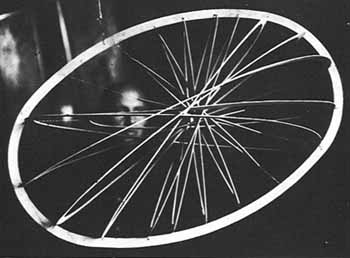

The kinetic artwork of Aleksandr Rodchenko.

While critics balked at the ready-made qualities of popularized cubism, the Exposition’s Russian pavilion offered a similar response to modern conditions. Aleksandr Rodchenko’s experimental environment called the "workers’ club" was assembled with "social-usefulness" and "economy" in mind [Hiesinger, Marcus, 80] and perfectly illustrated the attitude of the Soviet constructivist movement. Both Art Deco and Constructivism had technology at their core, but the constructivists’ chic was politically charged in a manner far distant from the decadence of department store vagary and the luxury of wanton shopping. The artists seated in the "workers club" would take it upon themselves to design a better society run by machines and the workers who powered them. This task was initially undertaken by Lenin, who commissioned artists to decorate the country with posters advertising Russia’s prowess. The upheaval of the Russian revolution had swept away the middle class, leaving the state as the only patron of the arts. Lenin believed that propaganda would launch his citizens toward greatness.

The state established the "higher state art training centre," or the Vkhutemas School, which came to be known as the ideological nucleus of Russian constructivism, and artists adopted Lenin’s belief in art with a purpose. The country’s artists had been familiar with the cubist agenda for quite some time and sensed that its universal signs and aura of idealism were adaptable to their society’s economic and spiritual gloom. To be true socialists, Russian artists needed to re-evaluate their position in society and apply their trade to the climate of the time. Modern artists would become workers amongst workers.

Aleksandr Rodchenko, creator of the "workers’ club", thought the constructivist’s aim should be "...to develop fully every way of addressing one’s fellows..." [Hughes, 95] and saw photography as the best medium for achieving this goal. Photography, which Rodchenko called "...instant socialism," [Hughes, 95] was a new technology that produced cheap, real images that were easily reproduced. He recognized a powerful quality in its factual documentation [Hughes, 95] and believed it was the perfect partnership of man and machine, politics and art. As Rodchenko extolled its virtues with the exclamation "Photograph and be photographed!" [Hughes, 95], Dziga Vertov heard his call.

page 1 of 3

|