Charley Chase with Viola Richard and Anita Garvin

in "Never the Dames Shall Meet" (1927).

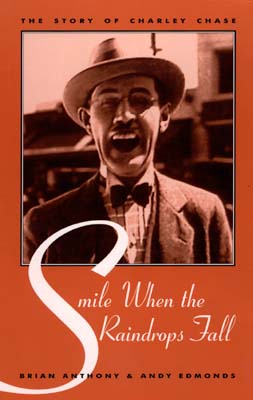

Now, thanks to a new book by Brian Anthony and Andy Edmonds, Smile When the Raindrops Fall, Charley Chase may once again receive some attention as one of the great screen comedians. The book is much more than simply the story of Charley Chase: it's also the story of the development of screen comedy. Chase was present through many of these formative years, first working in nickelodeons as a child, where he led the crowd in sing-a-longs, and later, after a vaudeville tour led him to Los Angelese, Chase wrote, directed, and starred in an astonishing number of short comedies. As such, the book is also the story of many of the producers, directors, and actors who participated in the creation of early screen comedies, such as Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Mack Sennett, Hal Roach, and Leo McCarey.

The book traces Chase's path to Hollywood, starting logically enough with his childhood in Baltimore. Pulled out of school after his father died, Chase worked odd jobs to help support the family. At the age of ten, he sang and danced on street corners for pennies and nickels pitched by passersby. By the age of twelve, he performed in vaudeville, where he had to shout to be heard over the unruly crowds. By the age of sixteen, he joined a major vaudeville troupe and left home to tour across the country (always sending money home to his mother). By the age of eighteen, Chase landed in Los Angeles after a vaudeville tour ended, and he decided to stay put. At this point in the early history of Hollywood, the city was "a rural, lazy town with dirt roads, orange groves, and soybean fields." Charley was there as the city and the film industry grew together.

As did many other vaudeville performers, Chase found the film producers hungry for talent both in front of and behind the cameras. Chase soon landed on the Mack Sennett lot, working as a writer. (Sennett thought Chase too "normal looking" to be an on-screen performer.) This tenure at Keystone taught Chase the "fast and furious" approach to filmmaking, and indeed Chase would become well known in Hollywood for his fast filmmaking technique: "Do it once but do it right," he said. However, at this point, Chase's work was indistinguishable from the other Keystone product. When Mack Sennett refused to give Chase a raise, he started looking for another studio to call home. After freelancing for a couple years, Charley landed at Hal Roach studios, supervising the production of shorts. This relationship with Hal Roach would prove to be crucial in Chase's career, for virtually all of Chase's best work comes from the next sixteen years while he worked for Roach.

Charley Chase with Muriel Evans

in "Nature in the Wrong" (1933).

First, Chase worked extensively as a director on Snub Pollard shorts. In 1921 alone, they made 20 or more comedies together. Charley largely stayed behind the camera, with only occasional bit roles; however, when Harold Lloyd left the studio, Hal Roach looked for someone to fill the void. He turned to Chase. Charley played two types of characters: 1) a "tall, lean, and handsome" young go-getter, an "All-American Boy" similar to the character played by Lloyd, and 2) an "Average Joe," a more mature version of the first character, who was typically involved in a domestic situation (often with a domineering wife).

As described by Brian Anthony and Andy Edmonds, "The Chase series humor was derived from situation and character, rather than relying solely on gags. Some of the films' best moments were built on subtle, throwaway gags that created a lasting and memorable impressions." Usually the plots "revolved around romantic complications. He was either trying to win a girl or playing an unwitting dupe in a marital triangle." Charley starred in a dozen or more shorts every year in the silent years. The transition to sound didn't slow him much, although his early sound shorts aren't considered among his best. However, Charley soon enough was back at the top of his form and starring in 7 or more shorts per year.

In the late '30s, Hal Roach decided to stop producing shorts and concentrate exclusively on feature length movies. As a result, after sixteen years of work for Roach, Charley Chase was unemployed. He would finish his career working for Columbia, starring in another series and directing shorts for The Three Stooges, among others.

Chase was only 47 when he died. He led a fast life style that constantly took its toll on his health. Known for womanizing and alcoholism, Chase was an habitual partier who rarely listened to his doctors--even when they warned him about his stomach ulcers. He ended up in the Mayo Clinic but that only slowed him momentarily before he was back drinking again. The dapper image he cut in the '20s quickly turned wrinkled and grey in the '30s. In many of his movies, he looks at least a decade older than his actual age. But Charley loved his lifestyle and he wasn't willing to compromise.

Smile When the Raindrops Fall is a fascinating trip through Chase's career. The writing is simple and unadorned, much like the filmmaking of Chase himself. The authors have a vast knowledge of Chase's shorts, and they meticulously take us through each year of his career (even including a lengthy discussion of some of the differences between the foreign and English language versions of the Chase shorts). Unlike many writers, however, Anthony and Edmonds aren't blinded by their subject. They recognize Chase's weaker efforts and separate them from his best. Short plot descriptions for many of the key shorts are provided in boxes set apart from the text, which has the effect of keeping the text itself from bogging down. In addition, the book includes an extensive Chase filmography, over 40 pages worth, and a list of the song credits for the Chase talkies. (Chase often sang a song in each of his shorts.) The book also includes a generous selection of stills (although the poor reproductions make the images murky) from a wide selection of Chase's movies.

Reading Smile When the Raindrops Fall whetted my appetite for watching some Chase comedies. I quickly realized I already had two Chase comedies on video tape--"Poker at Eight" and "Southern Exposure"--and I hadn't watched them in several years. (Nostalgia Merchant used to pad out their Laurel and Hardy videos with occasional shorts by other Hal Roach Studios performers, such as Chase, Thelma Todd, and Patsy Kelly.) Watching these shorts, I was pleasantly surprised at the bizarre plots and the subtle mannerisms of Chase. "Poker at Eight" in particular is frequently hilarious. It tells a story that defies a simple description, but I'll give it a try. Through a bit of coincidence Charley becomes convinced that he has the power of hypnotism. In order to get out of the house and attend a poker game with the boys, he tries the mumbo gumbo on his wife, urging her to be a "good fellow." His wife knows what he's up to and pretends to be hypnotized. And then, as Charley is literally patting himself on the back ("Am I smart or am I smart?") , his wife gets dolled up to go out on the town herself:

"What's the big idea?" says Charley, as he eyes her plunging neckline.

"I'm gonna step out and get a few laughs," she says.

"Looks to me like you're kinda gonna give the boys a treat," says Charley.

"Why not?" she says with a sly smile. "I'm a 'good fellow.'"

Much of the comedy in the short comes from Charley not knowing how to extricate himself from the situation. He ends up following his wife around town as she goes out dancing. The comedy comes out of the bizarre situation and the witty, unexpected dialogue that follows.

I know I'll be searching for more Chase comedies and I can only hope that someone will release more Chase shorts on video. These are truly some of the lost treasures of American cinema, and they deserve a larger audience.

Smile When the Raindrops Fall: The Charley Chase Story by Brian Anthony and Andy Edmonds is now available from Scarecrow Press, Inc., 15200 NBN Way, P.O. Box 191, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214-0191. Suggested retail price: $49.95 each. You can reach Scarecrow Press at (800) 462-6420.

|

Most discussions about the great film comedians instantly include Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and maybe even Harry Langdon, but the name Charley Chase rarely if ever enters the discussion. Unlike the other aforementioned comedians, Charley Chase didn't have a funny looking persona. He didn't wear baggy pants like Chaplin. He didn't have the blank, deadpan look of Keaton. He wasn't manic like Lloyd and he didn't move with a hesitant, unsure gait like Langdon. Charley Chase looked and acted pretty much like any normal person. Even the trade advertisements of the time played upon this difference: "Don't blush, Charley, but you're a good looking sunamagun. You aren't a cartoon or a caricature. Your face ain't lopsided, nor do you sport a Adam's apple the size of a pumpkin; you look like a real human and you act like one."

Most discussions about the great film comedians instantly include Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and maybe even Harry Langdon, but the name Charley Chase rarely if ever enters the discussion. Unlike the other aforementioned comedians, Charley Chase didn't have a funny looking persona. He didn't wear baggy pants like Chaplin. He didn't have the blank, deadpan look of Keaton. He wasn't manic like Lloyd and he didn't move with a hesitant, unsure gait like Langdon. Charley Chase looked and acted pretty much like any normal person. Even the trade advertisements of the time played upon this difference: "Don't blush, Charley, but you're a good looking sunamagun. You aren't a cartoon or a caricature. Your face ain't lopsided, nor do you sport a Adam's apple the size of a pumpkin; you look like a real human and you act like one."