| M O V I E R E V I E W B Y D A V I D N G |

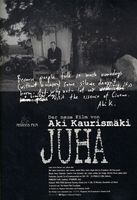

| | From Juha |

Scandinavian cinema has grown remarkably ascetic in the past few years. The Danish Dogma group started it all when it forswore any kind of artificiality – lighting, sound effects, music – from its filmmaking process. The resulting movies are technically innovative experiments that achieve documentary-like honesty. While Aki Kaurismakiís Juha is not a Dogma movie, it is inspired by the same self-imposed vow of chastity. Filmed in black and white, it doesnít contain a single word of spoken dialogue. It relies completely on facial expressions, dialogue cards, and incidental music to communicate the story. Kaurismaki (who is from Finland) wanted to make a movie that "could have been made in 1929." He has succeeded. He has flawlessly recreated the look, feel, and ambiance of a silent picture. However, he has chosen the wrong story to tell. Based on a classic Finnish novel, the movie focuses on Marja, a country wife who must choose between her gentle but backwards husband and a suave but dishonest gentleman from the city. The morality of the story is elementary and predictable. There is hardly a moment when we canít guess what the characters will do next. By pairing a simple story with an even simpler visual style, Juha merely reinforces its own lack of depth.

On an academic level, Juha can be studied in the same way as Gus Van Santís shot-for-shot remake of Psycho. They are both experiments: the directors are mimicking other directors. The way Kaurismaki composes his shots is lifted directly from silent films. He uses abundant close-ups; he has his actors exaggerate their facial expressions; and he cues the music to fit perfectly with shifts in emotion. He even uses a slower film speed to make his actors waddle in the same fashion as silent film stars. So technically proficient is Kaurismakiís imitation that, aside from the pristine quality of the print, Juha could easily pass as a relic of the 1920s.

| | | Poster for Juha. [Click poster to enlarge.] |

The screenplay deliberately creates caricatures whom weíve come to associate with the silent era. There is the idiot man-child, Juha (Marjaís husband), who is fundamentally a good man but is ignorant of his naivete. Marja fills the role of the fragile waif. Big-eyed and virginal, she depends completely on the idiot man-child for protection and emotional guidance. Finally, there is Shemeikka as the cunning Svengali who lures the waif with promises of wealth and high society. This will eventually pit Juha against Shemeikka in a showdown of urban decadence versus rural simplicity.

While Juha succeeds as an experiment, it fails to exist as a movie independent and separate from its inspiration. Kaurismaki has traveled back to the 1920s instead of bringing the 1920s to the present. He doesnít add any contemporary moral shading to his characters, contenting himself with broad strokes of good and evil. He also avoids technical innovation of any sort. Instead of enriching the style of silent film with elements of todayís technology, he regresses painfully towards primitivism. Itís like watching a gifted child act retarded. Like Van Santís Psycho, the director is obviously having all of the fun.

Juha could have benefited enormously from spoken dialogue. The subtleties of conversation would have added nuance to the flat story and would have given more personality to its wooden characters. The story of Juha begs to be hyperstylized. It is a blueprint that needs the interpretative creativity of a visionary. Kaurismaki is a visionary director. But instead of fleshing out the story, he has gone the opposite direction. Juha is a bare skeleton of a movie that is anatomically correct, but soulless.

[rating: 2½ of 4 stars]

|

|