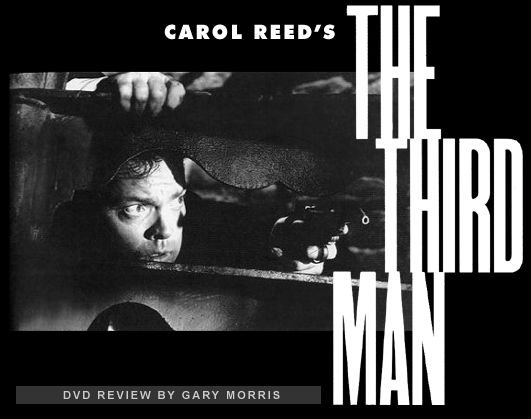

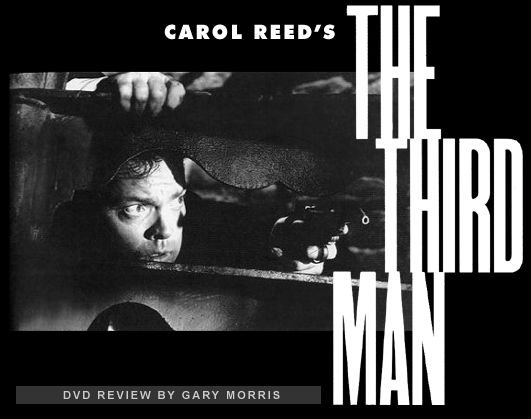

| DVD cover artwork for The Third Man.

[click photo for larger version] |

Lime chillingly embodies the chaos of a postwar world with his fascination with survival and triumph at the expense of any moral values. Reed captures this world with a camera that’s often grotesquely skewed, images of a Vienna seen almost exclusively at night, and supremely, the haunting presence of Lime as a literal shadow looming large over the pathetic daily lives of the ordinary people who are his victims. The informative production history on the DVD tells us that Welles was in a sense as "missing" as his character at certain pivotal points in the film. When he arrived in Vienna, he apparently disliked the sewer system and demanded a studio version be built in England. When Welles fled, the ingenious Reed improvised, casting assistant director Guy Hamilton as Harry Lime in shadow, having him dress in a black coat and hat and run across an arc light to project that large ominous shadow.

Welles is almost as famous for this role as for Charles Foster Kane, but his screen time is considerably less. While he makes the most of his scenes, which include a desperate run through a sewer system that looks like a Rembrant painting, The Third Man is as much about Martins’s dilemma, his awakening to the sordidness of life, and Anna’s refusal to awaken to it. Acting credits are superior throughout, from the leads to the decoratively weird characters who cross Cotten’s path and help flesh out this bizarre world. These include a carping old landlady perpetually wrapped in a blanket and a strange child who convinces a mob that Martins is a murderer.

The DVD includes the restoration of Reed’s original, more cynical opening speech. (David Selznick replaced it with a tamer version by Joseph Cotten, also available here.) There are also two radio drama versions, a solid stills gallery to go with the production history, a quickie restoration demonstration, concert footage of composer Anton Karas playing his famous zither ("He’ll have you in a dither with his zither!"), two different trailers, and subtitles for the hearing impaired. All considered, a masterful use of the DVD medium in the service of a classic film.