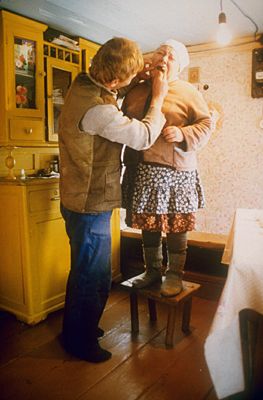

From Checkpoint (Alexander Rogozhkin, 1998). (Photo Credit: Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art) |

|

I don't know whether the makers are aware of it. For example, Ms. Sadilova, the director of Happy Birthday, mentioned in the post-presentation Q and A that the narrative structure of her film had been heavily influenced by Bunuel's Phantom de Liberte. Oy. Perhaps something was wrong with the translation on the Russian side. Ms. Sadilova delivers an engaging portrait of a dilapidated maternity hospital (in Russia kept separately from regular hospitals) in the last stages of collapse. This is a painfully familiar territory for anyone who has ever seen the real thing: primitive equipment, dubious hygiene, lack of privacy, lackadaisical personnel. The place is untouched either by modern science or by Western notions of doctor-patient interaction (e.g., one of the mothers is being kept in the dark about her baby's actual condition). Yet somehow, with a little wink and nod and scoffing of the rules, and a large dollop of borscht-like humanity, everybody pulls through.

The picture is done in a semi-documentary fashion, with many parts played by real-life patients. Ms. Sadilova seems to be patting herself on the back for delivering an unflattering view of Soviet backwardness, as perhaps she should. The cross-cultural gap is almost impossible to bridge. My companion stopped by the ladies' room after the show and overheard the following remarks from well-heeled MoMA patrons: "I didn't understand: why were those people there? Are they poor?"

Yet the same insistence on "as is" filmmaking and deliberately eschewing such "Hollywoodisms" as solid plot and deeper characterization (each of a dozen women, selected a la WWII fighter crew -- an intellectual, an Uzbek, etc. -- gets equal time) deprive the viewer of a more vivid, more emotionally loaded experience that the filmmaker could have otherwise achieved. Besides, the smirking at Hollywood does not sound very convincing with the final shots of happily hollering babies that invite oohs and aahs and signal a feel-good ending all over.

Alexander Rogozhkin's Checkpoint can hardly be accused of having feel-good sentiments. The festival notes liken it to Oliver Stone's Platoon, a comparison unparalleled in superficiality. Where Stone's film was pure Hollywood liberal agitprop, Rogozhkin goes out of his way to underscore the routine of an essentially dirty war, where soldiers are mostly waiting and killing time.

A platoon (that's the grounds for the comparison) of young Russian recruits gets involved in a stray killing of a local Chechen policeman during a routine house-to-house search. For the course of investigation, they are sent to a remote outpost -- a shack and a foxhole -- where they spend time playing practical jokes on one another and dodging the bullets of a lonely sniper in the mountains. Some are happy, buying hashish in the village; others are getting sex from a local mute girl, previously raped by Russian soldiers and now ostracized by the villagers. For both pleasures, they pay with actual ammunition. There are neither heroes nor anti-heroes here; they are just a bunch of kids without the foggiest of idea of what they are doing and why they are doing it. And the acting is impeccable.

Rogozhkin has a keen eye for detail: the Russian kids outwardly fashion themselves after US Marines and improvise rap enthusiastically. He has a Joseph Heller-like sense of humor: when the commander calls to ask the HQ for a supply of macaroni, the operator thinks this is a code word for "shells," which results in a hysterical word-play routine. He does not eschew drama and a tragic ending; yet his sense of proportion is skewed. Once again, you can't have an hour so deliberately eviscerated of suspense and atone for it with a predictable quick fix. You leave the theater feeling a little cheated, no matter that this is one movie with its heart in the right place.

As one of the few films on the war in Chechnya, and one that makes a honest attempt at being even-handed (the locals fight as dirty a war as the Russians do), Checkpoint caused a bit of a stir in the Russian media. However, most of the debate revolved around the history of the Russian role in the Caucasus and operated in categories that most Westerners would find of little interest. The same insularity applies even more to Lydia Bobrova's In That Land, another slice-of-life drama, this time from the Russian countryside.

Russian village life is Bobrova's favorite subject; her debut, Oh You My Geese, played well at The New Directions festival, also at MoMA, a few years ago. Just like Sadilova with Happy Birthday, Bobrova pulls no punches: her Russian village, with its feudal backwardness and the consumption of alcohol equivalent to a sizable American city, would seem to belong on the moon to an average Westerner. With a mixed cast of professional actors and actual villagers, Bobrova seeks to achieve the same effect as Sadilova; but at least In That Land has something that can be called plot lines and a leading character, Nikolai Skuridin, a put-upon cowherd whose persona is steeped in the great tradition of "little men" of Russian classical literature (e.g., Bashmachkin in Gogol's Overcoat). On the other hand, retelling the plot that revolves on a scheme whereby Skuridin is offered a free vacation in a Black Sea resort -- and then loses it -- is a thankless task here. What stays with the viewer is the hero's small hunched frame and eyes -- where hope died long ago. Plus his fellow drinkers, a jolly sentimental lot who die one after another so regularly that the farm manager enters their names on the This Year's Victims of Alcoholism poster displayed in his office. And an elderly mother who, desperate to marry off her daughter, finds her a husband in a prison camp. Of all the three "small" films, In That Land is perhaps one that is more than the sum of its parts. Its lack of outward drama is deceptively plain, just like the bleak landscape where it takes place. As I mentioned above, this film, too, raised a heated discussion on the condition of the Russian village in the media. It is unfortunate that, once again, its very plainness fails to reach across the cultural divide and ensures that it will remain a curiosity to an average Western viewer. Thus, I left the festival with mixed feelings. On the one hand, there is no reason why Russian filmmakers would specifically target Western audiences. Perhaps these three movies (not Khrustalyov, My Car!) -- and others like them -- will become the seed of New Russian Neorealism. But the chances for that are slim. Cut off from Western marketplace by their aesthetic strategies, these filmmakers continue to travel the festival circuit blithely, content with the acclaim of tiny audiences. And that's a shame, because there's nothing inherently "difficult" about their cinematic language. They deserve a wider audience; all they have to do is realize that lack of artifice is not the same as art.

|