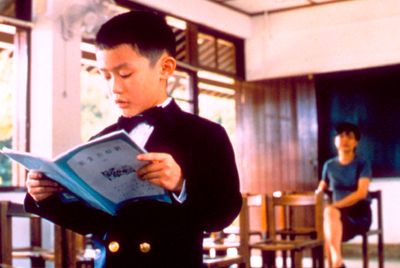

Jonathan Chang and Elaine Jim in Yi-Yi (A One and a Two). (© 2000 Winstar Cinema. All rights reserved.) |

|

Near the end of Edward Yangís comedy-drama Yi-Yi ( A One and a Two ), a businessman has had about as much as he can take from his wife, mistress, and failing career. In a drunken fit, he strips naked in the middle of his luxury apartment. This lonely, despairing moment is just one of many suffered by an upper middle class Taiwanese family whose members, ranging from an eight-year-old boy to an ailing grandmother, make up Yi-Yiís large ensemble cast. The movie begins at a wedding banquet where NJ, a family man and software company executive, runs into his ex-girlfriend in the elevator. Their chance encounter, awkward but engaging, sets the tone for the movie and precipitates a host of crises involving the rest of NJís family. Emphasizing the individual over the group, Yi-Yi , which takes its time at just under three hours, is more portraiture than family picture. With gentle precision, it illuminates those moments which we would never dream of sharing with our families.

The backdrop for these secrets and lies is Yangís bustling Taipei. Itís a city of contradictions, communal but isolating, traditional yet heartbreakingly Westernized (the snack joint of choice for NJís teenage daughter Ting-Ting is an American mall eatery named New York Bagels). Yang houses his characters in monstrous high rises from which they can survey the entire city. His Taipei is almost a sentient creature, watchful and observant of its inhabitants. Video surveillance cameras are seemingly everywhere recording daily life. Computer games designed by NJís company mimic violence on the evening news. Mirrors and glass lining the walls of apartments reflect home lifeís smallest details. Nothing goes unnoticed.

Yang isnít afraid of loose ends, and his movie can justly be accused of leaving too many of its stories unfinished. A friendship that NJ forms with a Japanese business partner ends abruptly (NJís colleagues sell him out) but we spend a good deal of time listening as they talk about music, love, and knowledge. For NJ, the brief bond they establish over an eveningís tea carries life-long significance. Yang-Yang has a similar experience in school when a girl walks into an auditorium, her skirt lifted momentarily by the door knob, and stands silhouetted in front of a movie screen as a voice intones "the origins of life." We never see her again but itís a moment that he (and maybe Yang himself) is likely to remember. True, the movie digresses but itís clear that its heart, and itís a big one, lies in its tangents.

The movieís title refers to musical improvisation, and Yangís script feels appropriately free-form. At Cannes, where he won the Best Director prize, he explained how the various stories took shape in his head over the course of fifteen years. Yi-Yi (A One and a Two) has the texture of something thatís been softened by time, though certainly not dulled. During a business meeting, NJ is asked how humans can master technology "when we havenít even fully understood ourselves." He doesnít answer. And neither does Yang, though he certainly has an idea. He comes closer than any other moviemaker this year to understanding and embracing those disparate people who make up a modern family.

[rating: 4 of 4 stars] Distributor Web site: Winstar Cinema New York Film Festival Official Site

|