|

|

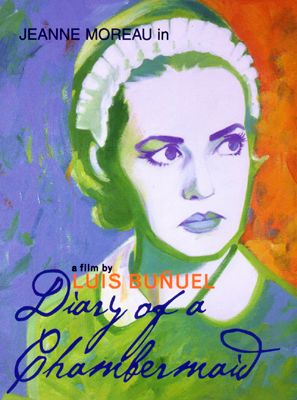

Despite his godlike status as one of cinema’s great artists and rebels, Luis Buñuel has only recently arrived on DVD. Criterion has just released two of his features, one in the high middle ground of his achievement (Diary of a Chambermaid), the other an Oscar winner that many feel is his greatest film (Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie).

Célestine (Jeanne Moreau) is a sophisticated domestic from Paris hired to work at an estate in provincial France in the 1930s. That all’s not quite right in the country is quickly evident when the driver who transports her, Joseph (Georges Géret), makes suggestive remarks, which, typical of Buñuel women, she takes in without being obviously offended. Her employers, seemingly standard-issue bourgeoisie on the surface, soon present to her a startling array of curious behaviors. The mistress of the house, Madame Monteil (Françoise Lugagne), is far more interested in the museum-quality objets d’art in her house than in her horny husband. When she isn’t polishing her urns, she’s busy conducting inexplicable chemistry experiments that at least one reviewer claims involve some kind of douche kit calculated to make her repellent to her husband. The frustrated Monsieur Monteil (Michel Piccoli) spends all his time hunting and knocking up servant girls, a plan he immediately tries with the indifferent Célestine. After grilling the newcomer ("Do you break things? Do you keep clean?"), Madame Monteil advises her to accede to the "whims" of the third member of this bizarre family, her aged father, Monsieur Rabour (Jean Ozenne). "Whimsical" is one word for this comic old pervert, who admires a butterfly and then blasts it with a shotgun in a startling early scene. He’s also an unrepentant fetishist, convincing Célestine to strut through his room in dominatrix boots while he drools over her calves.

Part of the film’s story is Célestine’s adaptation to this decadent world, but there’s much more going on than the gallery of grotesques suggests. Diary posits her as a threat to the insularity of the Monteils and their vapid way of life, a threat Moreau coolly limns in one of her most nuanced, restrained performances. (Fans of the wilder Moreau may be disappointed.) But the film also suggests that she may be a climber, strategizing on how best to move from maid to mistress. She resists, indeed triumphs over, every assault on her, which in the case of Monsieur Rabour takes the form of an overt attempt to strip away her very identity: "I’ll call you Marie," he says. "I’ve called all my chambermaids Marie. It’s a habit of mine. And not one I think I can break." Célestine can also be read as a more complex and modernized version of Susana, the title character of Buñuel’s 1950 melodrama about another, more obviously destructive interloper from the lower classes to the upper.

Diary kicks into high gear with a highly disturbing sequence, the rape and murder of a little girl whom Célestine has befriended. This event has the grim feel of a fairy tale, Little Red Riding Hood, specifically, with the little girl dressed in a hooded coat and gathering snails in the woods. It also occasions some powerful imagery, particularly a shot of a snail crawling over the dead girl’s body as she lies in the forest. Célestine suspects Joseph, the family’s driver who turns out to be a committed fascist. Her courting of Joseph in order to trap him into confessing is one of Diary’s most unsettling elements, as Buñuel keeps the viewer constantly guessing about her motives, with the suggestion that she may in fact be attracted to this butcher. While Célestine does her detective work, which necessitates going to bed with him, the household continues to lurch along – Madame Montiel with her curious experiments, her husband taking advantage of the dimwitted servant Marianne (Muni), Monsieur Rabour dying in a fetishistic frenzy.

Buñuel’s anticlerical strain is happily evident here as a minor motif in the form of a clueless priest (played by co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere) who yells "Goddammit!" and lectures Madame Montiel on the sinfulness of enjoying sex. The director’s antifascist impulses are also given play. He changed the time of the novel from the early 20th century to the 1930s to show that the combination of the haute bourgeoisie and dark human nature (as incarnated in the loathsome Joseph) provides fertile ground for the growth of fascism. Despite such serious elements – which are buttressed by the film’s clean, crisp, always credible atmosphere -- there’s a rich leavening of black humor throughout. The playful Buñuel even gets a brief personal revenge on the French police chief who censored Un Chien Andalou years earlier when Joseph, witnessing a fascist parade, repeatedly screams that censor’s name.

While neither as ambitious nor as absurdist as some of his more acclaimed films, Diary is still a worthy entry in the Buñuel canon, particularly in the DVD’s pristine widescreen (Franscope) transfer. The black-and-white imagery shimmers on the screen in this digitally restored print. Several extras sweeten the deal: a video interview with frequent Buñuel collaborator Jean-Claude Carriere; the transcript of a late 1970s interview with the director; the original theatrical trailer, narrated by Jeanne Moreau; and improved English subtitles.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is a mirror image of The Exterminating Angel (1962). In the earlier, black-and-white film, a group of high-society friends find themselves unable to leave a dinner, trapped in a comic-existential nightmare of paralysis. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, shot in color, finds a similar group who, through an increasingly weird series of circumstances, cannot consummate a meal. As fabulous as The Exterminating Angel is, the later film eclipses it as Buñuel’s ultimate statement on life’s pervasive ironies; he presents a world in which even the simplest acts – fornicating or, supremely, eating – become exercises in futility.

The film opens with the arrival of a group of friends for a dinner party at the mansion of Monsieur Henri Senechal (Jean-Pierre Cassel) and Madame Alice Senechal (Stéphane Audran). These friends are middle-aged married couple Monsieur Francois Thevenot (Paul Frankeur) and Madame Simone Thevenot (Delphine Seyrig); Madame’s younger sister Florence (Bulle Ogier); and Don Rafael (Fernando Rey), the ambassador to the imaginary banana republic Miranda.

This study in frustration slowly assumes cosmic proportions, as the ever-smiling group tromp from one place to another trying to have dinner. The first interruption is at the Senechals, where the hostess claims there was a mix-up in the dinner date. Next is a patronless restaurant where they discover the dead owner lying in state behind a curtain. The spiral continues in scene after scene: another restaurant, despite an army of other people enjoying their meals, claims to be out of everything, including coffee, tea, and milk; a group of soldiers conducting maneuvers outside the Senechal house arrive to be fed, again preempting the meal. Even in dream sequences, the conceit continues to dazzling comic effect, when the dumbfounded group is served rubber chickens that they bounce off the floor.

Leisurely subplots rip the veil – never exactly secure – from this allegedly respectable group. Like the other characters, the Senechals wander in a haze of self-absorption, so much so that they can’t even observe the simplest rituals of their class. They abandon the other guests for a woodland screw and can’t figure out why the guests have left. Florence is a drunken pothead. Rafael, Thevenot, and Senechal are drug dealers and users. Rafael and Madame Thevenot are also having a desultory, apparently never-consummated affair as the husband arrives to interrupt them without a clue about this attempted infidelity. Even the clergy isn’t safe from the film’s critique of hypocrisy. Monsignor Dufour (Julien Bertheau) has a gardening fetish, shedding his bishop’s gown for studly overalls to tend to the Senechal garden, an act that carries a subtle but unmistakable erotic charge.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie operates on multiple levels; like Diary of a Chambermaid, it keeps the audience guessing about a central matter – in this case, what is really happening to the group and what is fantasized or dreamt. Their expectations are constantly under threat, but mostly in quiet, subtle ways – no tea at the restaurant, for example. More dramatic versions of the threat are consigned to a series of brilliant dream sequences. In one, Buñuel reprises his frequent theme of the lost parent when a young soldier stops the group cold with his recounting of a dream – visualized in the style of a horror film – in which his mother, hidden in a closet, tells him the father he knows is not his real one, and that he (the boy) must kill that fake father. Later, a different soldier describes a similarly creepy dream where, encountering dead people in an empty, claustrophobic street, he cries out "Where are you, mother?"

Not all these dream sequences are horrific. In one of the most imaginative, the group’s very reality is challenged when, again sitting at a dinner table, a curtain suddenly opens to reveal them as the unwitting actors in a play complete with a screaming audience irritated that "they don’t know their lines!" This sends them scrambling in bewilderment yet again from their potential meal. Buñuel’s delight in his godlike manipulations of these confused creatures shines through this sequence. These scenes also show how sheltered they are from experiencing the world outside their plush self-created one, as the threats are mostly isolated safely in dreams. Even when the threat breaks through the bubble, as when they’re all arrested as they sit down to eat (of course), they’re soon released through the deus ex-machina of a high-up government official.

The film’s discursive structure allows numerous mini-melodramas to work themselves out. One of the best of these is Monsignor Dufour’s lethal encounter with a dying man he’s asked to bless, a man who turns out to be the murderer of his parents, who, he tells Dufour, treated him brutally. Buñuel’s anticlericalism is evident here and elsewhere – viz. a black-comic exchange between Dufour and a seemingly dim village woman (Buñuel perennial Muni) who describes how she’s always "hated Jesus!" But the climax of Dufour’s encounter with the dying killer is both tremendously shocking and inexplicably moving.

Despite the film’s trenchant view of the sins of the rich and those in their orbit, their activities, the constant sense of surprise in what they do, makes them so interesting that they take on an unexpected sympathy. Perhaps this is due to Buñuel’s more accepting attitude toward human folly at this late stage in his life. The justly celebrated scene, repeated several times, of the group walking together on a long road, sometimes in medium shot, sometimes in long shot, could be interpreted as both a comment on the pointlessness of their lives – they seem to be literally going nowhere -- and an appreciation of sheer existence even for these hapless characters. The latter may indeed be closer to Buñuel’s view; in the extraordinary closing credit sequence the sounds of their shoes hitting the pavement take on a musical, transcendent quality as the image fades while the sound remains.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is one of Rialto Pictures’ superb refurbishments of Buñuel, and The Criterion Collection has transferred this sparkling new widescreen print with subtle colors that seem as fresh as they were on the film's first release. (Rialto has three more restored Buñuels in the wings; with luck, these will also be released soon.) This is a double-disc set, and the extras are notable. Disc one has the film, a witty 24-minute documentary homage to Buñuel by his old pals Arturo Ripstein and Rafael Castanedo, the original theatrical trailer, and improved English subtitles. Disc two contains a Buñuel filmography and a fine new documentary, A proposito de Buñuel (Speaking of Buñuel), directed by Jose Luis Lopez-Linares and Javier Rioyo. The director’s life and work are covered in rich detail, and the viewer will come away with a strong sense of Buñuel as both a cinema giant and a deeply loved friend to many, including, surprisingly, several clerics who must have taken his famous statement "I’m an atheist, thank God" as an exercise in wit. Among the doc’s treasures is a beautiful quote from Buñuel’s biography that’s as good a summation of the man as any seen by this reviewer: "I’d like to be able to rise from the dead every ten years, walk to a newsstand, and buy a few newspapers. I wouldn’t ask for anything more. With my papers under my arm, pale, brushing against the walls, I’d return to the cemetery and read about the world’s disasters before going back to sleep satisfied in the calming refuge of the grave."

Diary of a Chambermaid and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie are now available on DVD from The Criterion Collection. Diary of a Chambermaid extras include video interviews with screenwriter and longtime collaborator Jean-Claude Carriere; a reprint of an interview with Buñuel about Diary of a Chambermaid; and an original theatrical trailer. Suggested list price: $29.95. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is presented as a double-disc special edition that includes the following extras: El Naufrago de la calle de la providencia (aka "The Survivor on the Street of Providence," 1970), a 25-minute documentary on Buñuel by his longtime friends Arturo Ripstein and Rafael Castenado; Buñuel's recipe for the perfect martini; A Proposito de Buñuel (2000), a new 105-minute documentary by Jose Luis López Linares and Javier Rioyo, based on Buñuel's autobiography My Last Sigh;and a theatrical trailer. Suggested list price: $39.95. For more information, check out the Criterion Collection Web site.

Both Diary of a Chambermaid and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie are also available on VHS from Home Vision Entertainment in letterboxed transfers with original theatrical trailers. Suggested list price: $29.95. For more information, check out the Home Vision Entertainment Web site.

|

|