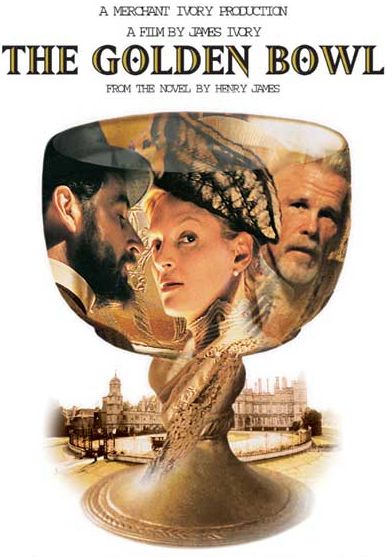

movie review by [click on photos Distributor Movie Production | With its length and complexity, The Golden Bowl represents the pinnacle of the Jamesian cannon. If you’re not a Jamesian scholar or fan, chances are you haven’t read it, or even heard of it. Never mind. The new Merchant-Ivory Productions adaptation is completely accessible, and it stars such familiar faces as Uma Thurman and Nick Nolte. The convoluted plot has been trimmed to a manageable 135 minutes (a little-seen 1973 BBC adaptation spans 4 hours). Rest assured, you won’t get lost in the story. But will you be moved? That’s a tricky question because the key events of The Golden Bowl, or of any James novel for that matter, occur not in the open, but deep within the consciences of the characters, so deep in fact that the characters themselves often do not register the changes. It is the job of that unmistakable voice, the narrator, to explain things and to clarify them.

So it seems that without James’ omniscient voice, The Golden Bowl would be a failed movie from the start. Like most of the other Merchant-Ivory adaptations, it is superficially faithful to the novel. The wealthy American robber baron Adam Verver (Nolte) lives alone with his only daughter, Maggie (Kate Beckinsdale). Together they move from one English manor to another, collecting priceless works of art. Maggie is engaged to Prince Amerigo (Jeremy Northam), a penniless Italian aristocrat. On the eve of their marriage, Maggie invites her old schoolmate Charlotte Stant (Thurman) to the wedding. Unbeknownst to Maggie, Charlotte and the Prince are former lovers. Time passes and while Maggie and the Prince raise their family, Charlotte and Adam Verver grow closer and eventually marry. Charlotte still longs for the Prince, and the two have many breathless encounters behind the backs of their spouses. These smoldering passions eventually ignite over the discovery of the titular object, a golden bowl, which appears early in the film as a possible wedding present for Maggie, only to be forgotten and to reappear much later in a different set of hands.

The romantic entanglements between the four protagonists are indeed complicated, and director James Ivory does an admirable job of keeping things clear for us, though he often resorts to facile symbolism to make his point. Ivory is a filmmaker who, in the words of one observant critic, has "no distinct visual style." Perhaps he doesn’t, but I think it’s more accurate to say that he lacks a real cinematic voice, preferring instead to conform to whatever author he happens to be adapting. Compare The Golden Bowl to two other literary adaptations, The Age of Innocence and Barry Lyndon, and we can see how a strong director can lay his own voice over a novel. Interestingly, Scorsese and Kubrick both use narration, though to completely different ends. In The Age of Innocence, Joanne Woodward’s conspiratorial voice-overs were lifted straight from the text and offered glimpses into the minds of the characters. The narration in Barry Lyndon was Kubrick’s invention entirely, and it reshaped the novel into a fatalistic exercise in detachment. Either way, the narrator provides a convenient mechanism whereby inner thoughts can be communicated with efficiency and little dramatic flair.

The absence of such a mechanism in The Golden Bowl necessitates several strident soliloquies, the worst of which is Maggie’s revelation of a dream. In it, she finds herself in a porcelain pagoda. The pagoda is beautiful but she’s trapped in it, and when she touches its walls, she senses a profound change within herself. Beckinsdale’s delivery borders on the ludicrous, but I doubt any actress could make these words ring true. Now, imagine the same scene but with Maggie’s dream told to us by a narrator (think Emma Thompson), whose voice-over is accompanied by images from Maggie’s daily life. Not only have we restored James’ voice, we have hinted at Maggie’s darker side without disrupting her essential innocence.

Early in the movie, Maggie urges her father to marry as a way of restoring "symmetry." The idea of balance is important to the story. In addition to the two central marriages, there are two other married couples that exist at the periphery. Fanny and Bob Assingham (Anjelica Huston and James Fox) are friends of the Ververs. Fanny is an American who has married into the English aristocracy and she is a confidant to both Maggie and Charlotte. The other couple is younger and also Anglo-American (played by Madeleine Potter and Peter Eyre) and wealthy. The role of these two outside couples is to comment on the two primary couples. With droll asides, they predict the eventual mess that will come of all this deception. We can also compare the married couples, particularly in terms of sexuality. We never see Maggie and the Prince or Adam Verver and Charlotte make love. Their apparent asexuality is contrasted with the Assinghams’ over-the-hill fumblings and the lewd exchanges of the younger couple.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s adaptation unequivocally conceives of Maggie and her father as purely innocent, the good guys, and the Prince and Charlotte as devious schemers. In an interview, Jhabvala said, "[The Ververs] are all goodness, and Henry James painted them as goodness." This take on the book is perfectly legitimate but it panders to the audience and underestimates our ability to deal with ambiguity. Many literary critics view the Ververs as the true aggressors who buy both the Prince and Charlotte with their money and then entomb them in their airless existence. The father-daughter team has incestuous undertones, and at one point, Maggie is reluctant to marry the Prince because it would mean spending less time with her father. Maggie, it can be argued, is an exemplary passive-aggressive predator. She wants to be close to her husband and her father, and she gets both without so much as thinking about it. Uma Thurman’s Charlotte is, in many respects, the opposite. She thinks she’s deceiving everyone with her plot to steal the Prince away, but in the end, she’s not as resourceful as she thinks. Money always wins out. Thurman, delivering on the promise of her performance in Dangerous Liaisons, fills Charlotte with a great vivacity that, at times, is so overpowering that Charlotte nearly recoils from herself in fear. Jeremy Northam’s Prince is also a sensual being who knows he’s capable of terrible things. In the movie’s single sex scene, the Prince and Charlotte make passionate love in a hotel room and feel little if any guilt afterwards. Nor do we because here at last are two people whose temperaments so perfectly match each others that nothing should keep them apart.

And herein lies the reason The Golden Bowl ultimately succeeds as a movie. Despite the loathsome things committed by these four characters, we like and care for each of them in different ways. Nolte’s Adam Verver has everything except true love, and the emptiness of his life echoes in the vast hallways of his mansions. His final scene with Maggie is the movie’s most emotionally complex. Fully aware of their spouses’ infidelity, but unaware that the other knows it, they quietly arrive at a solution that is terrifying in its simplicity. As with everything else in the Ververs’ lives, they have only to wish for something for it to happen. Charlotte, no matter how much she longs for the Prince, cannot have him, and it is this denial that makes us pity her. In the end, we see her giving tours of her husband’s art collection, art she cares nothing about, but whose role as symbol of wealth she will soon have to assume herself. As Charlotte declines, the Prince is elevated. He realizes that he loves his wife and returns to her albeit in a diminished form. There’s something sad in seeing this virile man (he drives his own car while the chauffeur sits in the back) reduced to a piece of property at the disposal of his wealthier wife. It’s a form of emasculation which the Prince accepts without complaint, and for this we admire him even more.

It should be noted that James Ivory used the paintings of John Sargent as visual inspiration. Sargent’s portraits depicted the nobles and American expatriates of the time The Golden Bowl takes place. While some critics have faulted Ivory for being too painterly a director, his recreation of Sargent’s work is entirely appropriate here. The Verver’s lifestyle is opulent, richly detailed, but ultimately inert. As in Barry Lyndon, their wealth is oppressive and ungainly. In the movie’s final scene, the camera iris closes in on the Verver’s art collection. It’s an eerie image for a movie with a happy ending. Even though we know everyone will be well cared for in the end, we get the feeling that they are all marching slowly and inexorably to their graves.

|