Tarantino's trail of bread crumbs leads to the French New Wave page two |

|

This detour and chance encounter do little for the plot but plenty for the tone. Later in the film, Charlie is kidnapped along with his girlfriend Lena: ostensibly a tense and sinister moment, it is one of the funniest sequences of the film. First our villains debate whether or not to show Charlie their guns in order to get him into the car. Then after capturing Lena, the action lapses into an hilarious digression full of backseat driving, kidnapping etiquette, and girl watching--not to mention a discussion about women's underwear. Rather than outwitting their captors, it's more or less Ernest's erratic driving that gets them pulled over by a motorcycle cop and allows the Charlie and Lena to cheerfully escape. All in all, it's a very enjoyable kidnapping! Piano Player doesn't conform to any of our expectations, and this forces us to experience the film on its own unique terms.

|

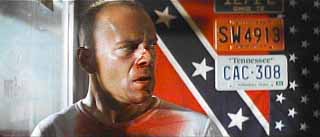

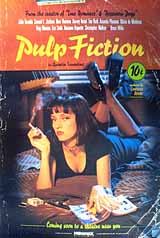

An examination of Truffaut's Shoot The Piano Player and Tarantino's Pulp Fiction is just one illustration of how Tarantino's work owes much to the New Wave. Like Pulp Fiction, Shoot The Piano Player is steeped in the lore of American crime novels of the 1940s. While Tarantino based his stories on pulp fiction in general terms, Truffaut's film is based on Down There, a novel from one of the pulpiest of pulp fiction writers, David Goodis. Both Truffaut and Tarantino situated their stories in modern settings, which serves both to place the genre conventions out of context as well as make them more apparent and therefore arbitrary. The first few moments of Piano Player illustrate this: the establishing shot is straight out of an American film noir, a man running terrified down a dark street one step ahead of a sinister pair of headlights. He stumbles, crashes into a lamp post, and is revived by a passing stranger. As they walk down the street, they start a conversation about marriage, the high proportion of virgins in Paris, and the stranger's wife and kids. They soon part company, and suddenly the film remembers to pick up where it left off as the man resumes his flight through the dark streets. The usually tight structure of Hollywood films is already being loosened by Truffaut.

An examination of Truffaut's Shoot The Piano Player and Tarantino's Pulp Fiction is just one illustration of how Tarantino's work owes much to the New Wave. Like Pulp Fiction, Shoot The Piano Player is steeped in the lore of American crime novels of the 1940s. While Tarantino based his stories on pulp fiction in general terms, Truffaut's film is based on Down There, a novel from one of the pulpiest of pulp fiction writers, David Goodis. Both Truffaut and Tarantino situated their stories in modern settings, which serves both to place the genre conventions out of context as well as make them more apparent and therefore arbitrary. The first few moments of Piano Player illustrate this: the establishing shot is straight out of an American film noir, a man running terrified down a dark street one step ahead of a sinister pair of headlights. He stumbles, crashes into a lamp post, and is revived by a passing stranger. As they walk down the street, they start a conversation about marriage, the high proportion of virgins in Paris, and the stranger's wife and kids. They soon part company, and suddenly the film remembers to pick up where it left off as the man resumes his flight through the dark streets. The usually tight structure of Hollywood films is already being loosened by Truffaut.