|

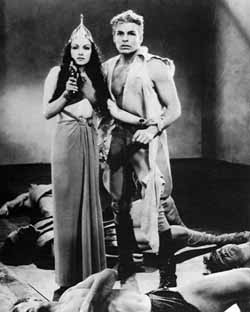

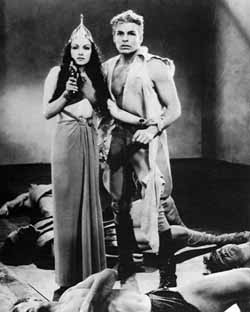

Princess Aura and Flash Gordon

from Flash Gordon.

Aura lacks Dale’s fragile beauty and that’s what makes her much more appealing to me: she’s strong, forceful, uninhibited. And in case the sexual energy behind the eyeline matches was missed by some of the younger boys (no doubt, the film’s largest constituency), Stephani sets up a second, less subtle triangle. Ming, rising from his Shell-Oil-shaped chair, approaches Dale and openly confesses his desires: "Your eyes, your hair, your skin. I’ve never seen one like you before. Ahh, you are beautiful." He stretches twisted, gnarled fingers toward her, but before he can touch her purity, Flash leans in and intervenes. "Keep your slimy hands off her," he shouts, underlining the text’s fear of race-mixing and the privileging of the white body as status symbol and power.

Ming, the alien outsider, and Aura, the desiring female, are both transgressive figures, needing to be somehow contained by the text’s racist and sexist ideology. Ming is clearly Asian-coded in Alex Raymond’s Sunday strips—his skin is colored yellow; in the film, "Asian otherness" is implied through Ming’s appearance (the mustache, the exoticized fingers, the squinting eyes, and the Fu Manchu mustache all recall Sax Rohmer’s Asian mastermind bent on world domination), his stereotypical manner (inscrutable and deadly), and the far-eastern sounds to the names that inform his identity (Mongo, a diminutive for Mongolia; Ming, a reference to a series of imperial dynasties in China’s history). Ming’s desire for Dale and Aura’s desire for Flash spins the narrative in dynamic directions, sometimes pitting daughter against father, other times aligning them in their common lust.

Ming and Aura’s desired transgressions change the overall arc of the narrative. Initially, the plot’s concerned with our heroic threesome traveling to Mongo to prevent it from colliding with Earth, but Dr. Zarkov solves that dilemma in Chapter Two! Thus, the Ming/Aura axis of desire transforms Flash’s quest. He isn’t just a square-jawed hero saving the world from a megalomaniac bent on destroying it. The plot is more concerned with Flash’s ability to protect Dale’s virtue from Ming and her life from Aura. The close of this chapter foregrounds the former conflict. Flash races through a cave tunnel to prevent the drugged Dale from marrying the lecherous Ming. As a gong tolls the approaching nuptials (thirteen being the unlucky number), Stephani crosscuts between the ceremony—an Egyptian looking affair with weird Cleopatra statuary and temple fineries (actually set design leftovers from Universal’s earlier The Mummy [1932])—and Flash trapped in the clutches of a lobster-clawed dragon!

See Flash Gordon menaced by a terrible crab monster,

an excerpt from Flash Gordon.

(Animated GIF, 25 frames, 140 KB)

Chapter Three solves the cliffhanger by expanding the traditional crosscut of two parallel planes of action into three. (SPOILERS ahead.) In typical serial fashion, the audience gains greater knowledge as time is extended and additional edits open up the shorter closing sequence to Chapter Two. Suddenly, a prior and previously unseen Prince Thun (a leonine-figure who would be at home in Oz) rumbles through the caves, lugging a blaster. He stuns the monster, frees Flash, and together they enter the back end of the temple, toppling the shrine to the Great God Kalo, and thus disrupting the wedding.

Flash gets electrocuted in Flash Gordon.

Later, in Chapter Eight, a third triangle is added to the mix, as the portly Prince Barin (Richard Alexander), the rightful heir to Mongo—his father was killed by Ming and he himself banished—admits his love for Aura to Flash! It all happens during a crazy sword duel: Ming had guaranteed freedom and the choice of a bride to the victor, and Barin, disguised under a black hood, fights his best friend in order to win the woman he loves, or, should he lose, to meet his own death wish and be put out of his "misery." Aura further troubles the triangle by surreptitiously helping Flash fight a dreaded Orangopoid (another one of Ming’s tests—actually, a guy in a monkey suit with a rhinoceros horn on his head). Disobeying her father’s wishes, Aura attacks the creature, launching a spear into the all-too-weak white spot along its neck. This subtle form of patricide—going against the law of the father—will play out in the rest of the narrative as Aura will move from loving Flash to finally loving Barin and reforming her bad-girl ways.

But it’s not just these complex love triangles that make this such a great serial. It’s much more than that. Larry "Buster" Crabbe is wonderful as Flash Gordon. Unlike the bourbon-soaked flab of so many other serial heroes (check out Columbia’s Batman and Robin [1949] for the greater-gut look), Crabbe actually is a comics-super-hero come to life. A former Olympic swimming champion, the bare-chested, bleached-hair Crabbe is resilient, strong and vulnerable. He also possesses the star-quality of a Douglas Fairbanks: he has the athletic verve, pep, and most importantly sincerity of the earlier star. Never once is Crabbe’s tongue in his cheek, never once does he hold himself above the story’s world. Instead, Crabbe makes the fantastic real. We believe that he can fly a spaceship, we believe that the perils he fights against are real, and most importantly, we believe in him, as the embodiment of Alex Raymond’s character.

Finally, Ralph Berger’s art direction is stunning, an appealing blend of styles: the interiors to Ming’s fortress are a combination of Asian and Egyptian architecture. The exteriors are borrowed from James Whale’s Frankenstein. The spaceships burst from the pages of Buck Rogers and Universal’s earlier SF flop Just Imagine (1930). The Atom Furnace room, where Thun, Flash and Barin are held work slaves, modifies the urban angst and alienation of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1925). And all of the various monarchs are amalgams of literary history. King Kala, ruler of the shark people, resembles a New York gangster in Caligula robes. Prince Barin, with his chiseled breast plate and gleaming headgear captures the glow of a Roman warrior, and the laughing, lustful King Vultan strikes a pose somewhere between a winged Friar Tuck and the gluttony of Henry the Eighth. Flash Gordon benefits greatly from foregoing other serials’ reliance on location-shooting in Bronson Canyon. The use of Universal’s soundstages combined with Berger’s art direction create a unique comic-book reality that still, sixty years later, looks great, hot and very sexy.

The Serials: An Introduction

Page 1: In the Theaters

Page 2: The Beginnings

Page 3: Enter Flash Gordon

Page 4: The Golden Age

Page 5: The Downfall

The Phantom Empire

Flash Gordon

Dick Tracy

The Fighting Devil Dogs

Zorro's Fighting Legion

The Shadow

Mysterious Dr. Satan

Spy Smasher

Perils of Nyoka

The Tiger Woman

Serials Web Links

|

Universal’s Flash Gordon (1936) extended the New Deal era’s aerial emphasis.

Universal’s Flash Gordon (1936) extended the New Deal era’s aerial emphasis.